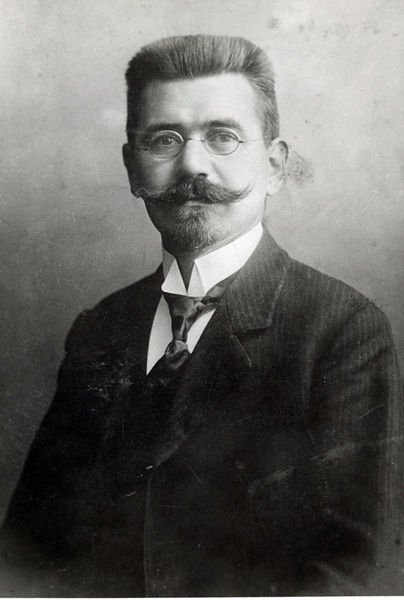

Elder Jacob Aron Rempel was probably one of the most important personalities among the Mennonites of Russia in the 20th century, both in terms of his theological education as well as in his extraordinary personality and public activities. In 1929 he was arrested by the USSR’s secret police force (GPU) for his religious affiliations. He spent the next twelve years in exile and in prison, before his execution in 1941.

Early Life

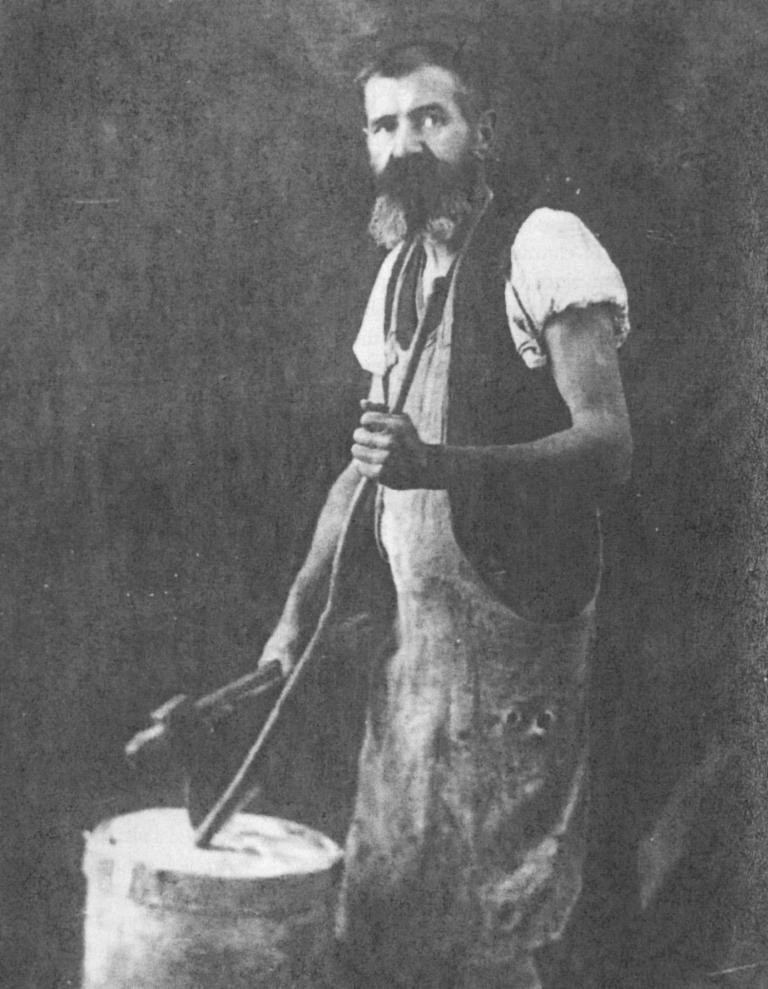

Rempel’s father and ancestors were farmers, but his father moved into business and he was a mill owner for a short while. In 1893, however, he went into bankruptcy and was plunged into bitter poverty. The eldest son in a family of 13 children, Jacob was hired out to a local farmer as a stable boy at the end of his time at the village school in Schöndorf.

Despite these hardships, he became a teacher through disciplined, self-education. With the help of a scholarship from a wealthy mill owner (John Thiessen, Ekaterinoslav) he was able to study for six years in Basel. Rempel then returned to Russia in 1912 and began teaching at various high schools in Chortitza, Jusowka, Nikopol and Ekaterinoslav. He also served as a preacher of the Mennonite church at Ekaterinoslav.

In the spring of 1920 Rempel was appointed as a professor of German at the University of Moscow. At the same time he was elected by the congregation of New Chortitza as an elder. He accepted the position with great enthusiasm and was ordained on May 2, 1920. This marked the beginning of a lively activity in his local congregation and in the neighboring communities.

Church Work

At the General Mennonite Conference in October 1922, Rempel was elected Chairman of the Commission for Religious Affairs (KfK). It now fell to him and the KfK to represent the Mennonite churches of Russia to a strongly anti-religious Communist government in an effort to free Mennonite young people from the new military laws and military service. Beyond this, it was his task to hold together the Mennonite communities of Russia who were being torn apart at the time, seeking to maintain ties with each other.

Under his leadership, a General Mennonite National Conference took place in Moscow in January 1925. The conference was later referred to as “Second Martyr Synod of the Anabaptists.” The Communist rulers had taken careful note of the Mennonite church leaders in Moscow and did not let them out of their sight.

One by one, they soon fell into the hands of the Communist officials. Of a total of 86 participants in the January conference, most were arrested at some point between 1929 and 1941 and imprisoned, banished, or killed. Only 18 managed to emigrate to Canada or the United States.

At the conference Rempel earnestly requested that he become a less publicly visible leader within the church. Therefore Alexander Ediger was elected as Chairman of the KfK. But Rempel was asked to continue to direct the work that had been started, especially the organization of a seminary, which was not permitted by the government.

In June 1925, Rempel participated in the first Mennonite World Conference in Basel as a representative of the Mennonites of Russia, and then traveled for almost four months visiting Mennonite congregations in Germany.

Arrest and Exile

In Russia, the political pressure on the congregations and the preachers became heavier from year to year. Although every citizen was theoretically allowed to hold religious convictions, any form of religious propaganda was banned.

Nearly all Mennonite church activities were labeled as anti-revolutionary. All preachers had to register as a “religious servants” and thereby lost the right to vote. They were also denied any possibility of earning a living. Nevertheless, taxes on churches and preachers were raised higher and higher, with the goal of depriving both the preacher and the community as a whole of basic resources.

In August 1929 taxes of nearly 800 rubles were imposed on Jacob Rempel, whose annual income stood at just under 360 rubles! He knew that he could never raise this amount of money. In order to avoid his inevitable arrest, Rempel, who was a church elder, escaped from Grünfeld on September 8, 1929.

On October 13, his entire property was confiscated and the family driven out of Grünfeld. Nevertheless, Rempel could write: “[I] thank God that I may suffer for His name’s sake …I want to go and thank God … that we may experience such an opportunity to prove that our faith in God is not connected in any way to earthly goods. . . “(Quoted ML 3, 473).

In November 1929 Rempel tried to emigrate with his family out of Russia through Moscow, since he had already received entry documents from the German consul in Kharkiv. But on November 16, 1929 Rempel was arrested in Moscow by the GPU (Joint State Political Directorate—the USSR’s intelligence service and secret police) and accused of being an instigator and leader of the emigration.

On June 9, 1930, after seven months in custody for his alleged “anti-Soviet and counter-revolutionary activity” —on the basis of the infamous Article 58, penal code that broadly defined counter-revolutionary activity and prescribed harsh punishment—Rempel was sentenced to ten years in a concentration camp on the island of Solovki in the White Sea.

In April 1931 he was transferred from here to a camp in the south (Alma Ata region). In the midst of a second transfer in January 1932, Rempel escaped from the train in the area of Omsk and fled to the Mennonite colony of Ak Metschet (Turkestan).

Here he lived as a free citizen for almost four years under the false name of Sudermann (his wife’s name). During these years he also visited the Mennonites in the Trakehn settlement (in Pyatigorsk, Caucasus) and met there with his wife. However, someone betrayed him to the NKVD police force and on March 13, 1936 Rempel was arrested once again.

Final Years

He came via Moscow to a jail in Vladimir. Then in November of 1936 he was returned to Pyatigorsk (Caucasus) and interrogated. Before a show trial he was accused again of “counter-revolutionary and anti-Soviet activity” and condemned on April 18, 1937 to be executed.

After submitting a plea for grace, the sentence was reduced to 10 years in prison followed by five years of deprivation of all civil rights. Rempel was sent back to Vladimir, and then in April 1939 came to the state prison in Orel (500 km south of Moscow).

Up until June of 1941 he was permitted to write letters to the family. In one of these letters he wrote: “I know that God has decided what is best for me, so I want to carry this burden with dignity” (quoted Heidebrecht, p 265).

In one of his last letters he wrote: “You can put me in chains, hit me, cut off my head, but no one can take my faith. . . away from me. From a stable boy to professor,. . . and now [in jail] I’m at the pinnacle of my life “(quoted Rempel, p 474). In general, however, religious commentary was prohibited, so his letters instead focused on the life and activities of his family and of his longing to see them again.

On September 8, 1941, as German troops approached Orel, Rempel was again convicted by the Military Collegium of the Supreme Court of the USSR for crimes under Article 58, paragraphs 4.6 and 10 of the Criminal Code of the RSFSR and sentenced to death.

He was shot on September 11, 1941, along with 157 other prisoners. Almost 50 years later, on March 15, 1989, a resolution of the USSR Prosecutor’s Office exonerated J. A. Rempel.

Submitted by Peter Letkemann.

Sources: Alexander Rempel, “Rempel, Jakob Aron,“ in Mennonitisches Lexikon [ML], Bd. 3, S. 470-474.

Peter Rempel, Ältesten J.A. Rempel’s Lebens- und Leidensgeschichte. Selbstverlag, o. D.

Herman Heiderbrecht, Auf dem Gipfel des Lebens, Vom Stallknecht zum Professor, vom Träumer zum Märtyrer. Bielefeld: Christlicher Missions Verlag, 2004.

Peter Letkemann, A Book of Remembrance – Mennonite Victims of the Second Revolution, 1929-1941. (in Vorbereitung)

Tatiana Plokhotniuk, “The Life and Death of Jacob Aron Rempel, An Example of Mennonite Resistance to Destructive State Power”, unveröffentlichter Referat an der wissenschaftlichen Konferenz “Molochna 2004: Mennonites and their Neighbours (1804-2004),“ held in Zaporizhia, Ukraine, 2–5 June 2004.

Aron A.Töws: Mennonitische Märtyrer der jüngsten Vergangenheit und der Gegenwart. Winnipeg: Selbstverlag, 1949, S. 30-46.

Another useful English-language source is Hope is Our Deliverance by Amalie Enns and Alexander Rempel (2006). This volume includes English translations of the letters that Jakob Rempel wrote to his wife, Sonja, and their children during his imprisonment and exile.

What incredible suffering and compelling testimony. Makes me realize how precious faith and freedom are. Thanks for sharing this difficult narrative.

Thank you for sharing this compelling narrative of one of our martyrs. JAR was my maternal grandfather, whose legacy was kept alive and well within the Rempel family, and now more recently in a memorial scholarship at CMU in Winnipeg.

A great man of God with an encouraging faith