Last week’s post on the main Bearing Witness site narrated the outlines of Russian Mennonite Jakob Aron Rempel’s journey from visible church leader to Soviet prisoner. After a successful career as a professor and church representative, the last twelve years of Rempel’s life were spent in prisons, labor camps, and even a brief period in exile after a successful escape attempt. Eventually, Rempel was executed along with 157 others by order of Joseph Stalin on December 23, 1941, in what is now known as the massacre of Medvedevskij Les.

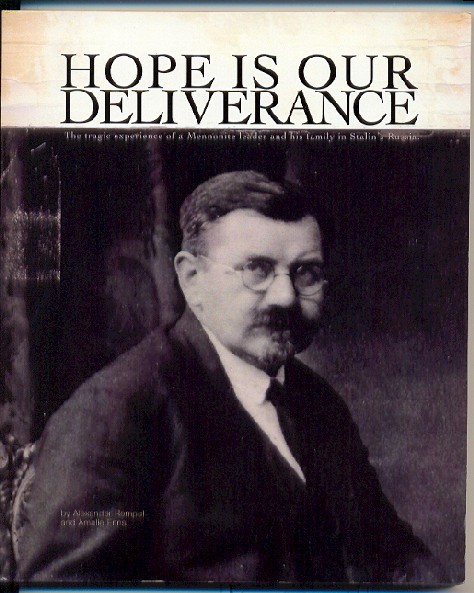

A book written by Alexander Rempel and Amalie Enns, Jakob A. Rempel’s son and granddaughter, offers a more complex portrait that fleshes out some of the details of this period, including the impact of twelve years of separation between Rempel and his wife and children.

Hope is Our Deliverance: The tragic experience of a Mennonite leader and his family in Stalin’s Russia is ultimately a heartbreaking account of the life of the Rempel family, although there are, of course, inspiring elements as well. But twelve years is a long time to hope in seemingly hopeless circumstances, and the story carries a very different narrative form from more traditional martyrdom narratives where believers died passionately professing their faith.

In the introduction, Enns writes,

“Perhaps the reader may complain that there is an almost monotonous repetition to these voices of the past, that their suffering was never ending, that it is best to put the past to rest. Yet each individual tale of suffering is singular. Every voice has a unique story to tell.”

Indeed, Hope is Our Deliverance contributes a particularly detailed perspective to the current collection of published Russian Mennonite history from this period, much of which is focused on stories of immigration from Russia to Canada or South America. Those stories offer us as readers a sense of closure; those who suffered were given a chance to begin again.

In contrast, Hope is Our Deliverance leaves the reader with a sense of the daily wear and tear Rempel and his family experienced; of the high personal cost for Rempel’s wife, Sonja, who carried the responsibility of raising and providing for the family’s six children; of the poverty and instability that Rempel’s arrest precipitated in the family; of the loneliness that threatened to break Rempel’s spirit; of the ostracism the family bore; of the contours of faith when despair seemed like a perfectly reasonable alternative.

The first two-thirds of the book is a well-written and detailed account both of Rempel’s church activities before his initial arrest in 1929 as well as the events that shaped his life and his family’s life over the next twelve years. An impressive collection of photos illustrates the changes in the family and in Rempel over the course of his imprisonment and exile.

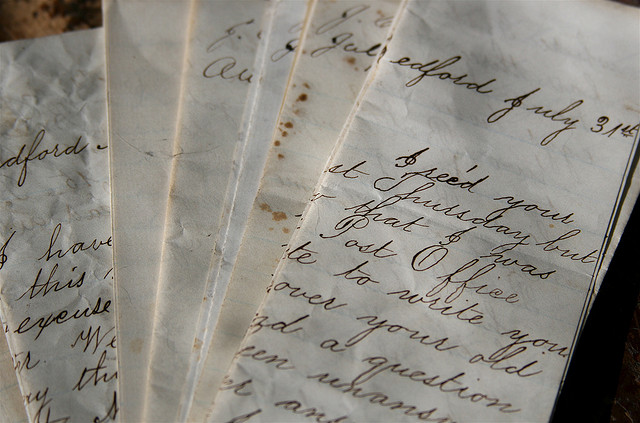

The final third of the book is a translated collection of letters written by Rempel between 1929 and 1941. Although the letters were censured by Russian authorities for frequency, length, and content, they provide an unusual window into the emotional life of a family torn apart by an oppressive state structure and compose an especially valuable resource for English-language readers.

Given the context of censorship, Rempel’s letters rarely spoke directly to his faith. Instead the letters more explicitly reveal the evolving shape of a family’s relationship across distance and suffering, while also testifying to the bare bones of a faith that undergirded Rempel’s life even when all of the positions, activities, community structure, institutions, and public practices were stripped away.

As a whole, the book is an extremely honest account of spirituality and family relationships in exceptionally difficult circumstances. Although he never mailed it, Rempel wrote a letter to his brother that ended by quoting Jesus’ plea on the cross, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” Yet near the end of his life, Rempel continued to affirm his faith as sustaining, enduring when all else had been lost. In one of his final letters to his family, Rempel wrote, “You can put me in chains, hit me, cut off my head, but no one can take my faith…away from me.”

Hope is Our Deliverance is highly recommended for anyone interested in Russian Mennonite history during Stalin’s rule, in the intersections between costly discipleship and family life, or in the exploration of spirituality and Christian faith in situations of oppression and hardship.

Canadian residents can borrow Hope is Our Deliverance from Mennonite Church Canada, and it can also be found in the libraries of the following institutions: Mennonite Historical Library (Goshen, IN); Anabaptist Mennonite Biblical Seminary (Elkhart, IN); University of Waterloo (Waterloo, ON); Eastern Mennonite University (Harrisonburg, VA); Mennonite Library and Archives-Bethel College (North Newton, KS); Fresno Pacific University (Fresno, CA). Unfortunately, no digital copy exists at this time.

Rempel was not executed in 1953 as the following sentence implies “…. Rempel was executed along with 157 others by order of Joseph Stalin on December 23, 1953…” See https://www.martyrstories.org/jakob-aron-rempel/ — It was in 1941.

Thank you for the correction!