In 1948 the assassination of Liberal political candidate Jorge Eliécer Gaitán touched off a ten-year civil war in Colombia. In nearly the same year, Colombians joined with Mennonite missionaries to form the first Colombian Mennonite congregations. But the civil war cast a long shadow over the church’s early years. Because Protestantism was seen as a threat to the stability of Colombia’s already-strained unity, Colombian Mennonites faced significant opposition from municipal authorities, Catholic priests, and their own neighbors.

Tulio Pedraza, a blind man who was also the town’s coffin-maker, was one of the first Mennonite converts in the town of Anolaima. Pedraza and his wife, Sofía Álvarez, were baptized in June of 1949 and they became one of the church’s founding families. Their commitment to the church brought extreme difficulties to their household, however.

Although blind, Pedraza had developed a business selling coffins in Anolaima. After his conversion in 1949, however, the priest declared Pedraza’s “Protestant” coffins unsuitable for Catholic burials, and he prohibited all parishioners from frequenting Pedraza’s business. In order to provide for coffin production, the priest brought in another carpenter from out of town. Pedraza’s business was ruined. Raúl Pedraza remembers his father’s experience of losing the business:

Although blind, Pedraza had developed a business selling coffins in Anolaima. After his conversion in 1949, however, the priest declared Pedraza’s “Protestant” coffins unsuitable for Catholic burials, and he prohibited all parishioners from frequenting Pedraza’s business. In order to provide for coffin production, the priest brought in another carpenter from out of town. Pedraza’s business was ruined. Raúl Pedraza remembers his father’s experience of losing the business:

There was an extremely harsh reaction [to Tulio’s conversion]. The first to react strongly was the priest…. Then the priest said from the pulpit that he would not preside over the funeral of anyone who bought their coffin from Marco Tulio Pedraza. So obviously, sales dropped…There were one, two, or three cases where, out of ignorance maybe…and because of friendship, some went and bought their coffin from Papa. And the priest didn’t want to do their funeral service….So they had to go to one of the towns that surrounded Anolaima and have the service there….

This priest…had been starting a parish in a small town that was called Villaní. And there he had met a carpenter….And the priest went to this town, brought the carpenter, managed to get him [to come], helped him get a house, helped him buy tools, really he organized everything for him. All with the intent that this carpenter would become the competition for my father. The priest had all the power! Somewhere around 1950, 1951, my father couldn’t do it anymore. He had debts with his suppliers.

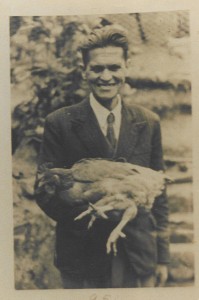

In the face of the loss of his coffin business, Pedraza and his wife attempted to start a number of other ventures, including a bakery, a chicken farm, and a candle-making operation. Unfortunately, none of these were able to supply their family with the same level of stability they had had with the coffin business. Raúl Pedraza remembers this period as being heart-breaking for his father, leading him to become more and more discouraged.

Tulio Pedraza’s life was also threatened a number of times during religious processions in Anolaima. Although the family believed the threats were hollow, they did not want to risk injury, so Tulio and Sofía spent the night on the grounds of the missionary-run Mennonite school in nearby Cachipay.

Despite these difficult experience, Pedraza was became known for his demeanor of love in the face of much hatred. Missionary Gerald Stucky wrote the following about Pedraza two years after he first lost his coffin business:

The persecution has continued. Tulio’s children were humiliated in the public school because they are Protestants. His property and the lives of his family have been continually menaced. People who were his friends now refuse to speak to him on the street; stores refuse to sell to him; he has become an outcast for the cause of Christ. In spite of this Tulio continues firm in the faith, trusting in the Lord day by day. He holds no evil in his heart towards those who have worked evil against him. He continues to witness to the light he found in Christ. Tulio is a living witness to the power of the Gospel to overcome evil with good.

Pedraza’s son remembers how his father befriended the carpenter who was set up as his priest-approved competitor. Instead of shunning the man who would ultimately take away all of his customers, Pedraza helped him establish his business, even selling him his tools. Pedraza’s actions made such an impression that the rival carpenter donated the coffin for Pedraza’s burial upon his death in 1964 and attended his funeral, even though it was an explicitly Mennonite service. Pedraza’s choice to love his “enemy” testified to the depth of his faith in Jesus Christ and the strength of his convictions, no matter what the circumstances.

Submitted by Elizabeth Miller.

Sources: Raúl Pedraza Álvarez, “Hechos y crónicas de los menonitas en Colombia,” Vol. 1., manuscript; Raúl Pedraza, interview by Elizabeth Miller, 16 May 2011; Gerald Stucky, “Tulio Pedraza,” 1952.